Feature

Wartime Nursing Posters

How depictions of nurses shaped public sentiment towards war

Posters have punch. They have color. And, where they depict nurses and nursing, they provide an important historical record of the many changes that have taken place since Florence Nightingale first tried to bring respectability to a once disreputable profession.

Although eventually overshadowed by radio, TV, and the Internet, posters have been a vital form of communication since the printing press first made it possible to mass-produce them. Clever graphic design and striking images can deliver a wallop that a thousand words couldn’t convey.

During the first half of the 20th century, wars and military recruitment campaigns were a rich source of poster art featuring images of nursing. Governments and military organizations hired prestigious painters and illustrators to help recruit nurses, persuade the folks back home to buy war bonds, or just encourage the proper patriotic spirit.

Nurse Recruitment

Military nurses are often in short supply in wartime. During many of the major wars of the last century, poster images of heroic nurses sought to inspire young women to volunteer.

One example from WWI, now part of the Smithsonian collection, is the 1918 poster “The Comforter” (above, left) by Gordon Grant, which depicts a nurse on the front lines, caring for an injured soldier. It captures the generous spirit of nursing while conveying (in carefully romanticized fashion) the real dangers wartime nurses sometimes face.

It would be hard to find a more glorified image of nursing than “The Spirit of America” (above, right), a 1919 recruitment poster for the American Red Cross. With its flag-waving young nurse in a diaphanous gown, her eyes lifted to heaven, this lithograph by Howard Chandler Christy is a prime example of how wartime poster art spurred viewers to action and fostered patriotism at the same time.

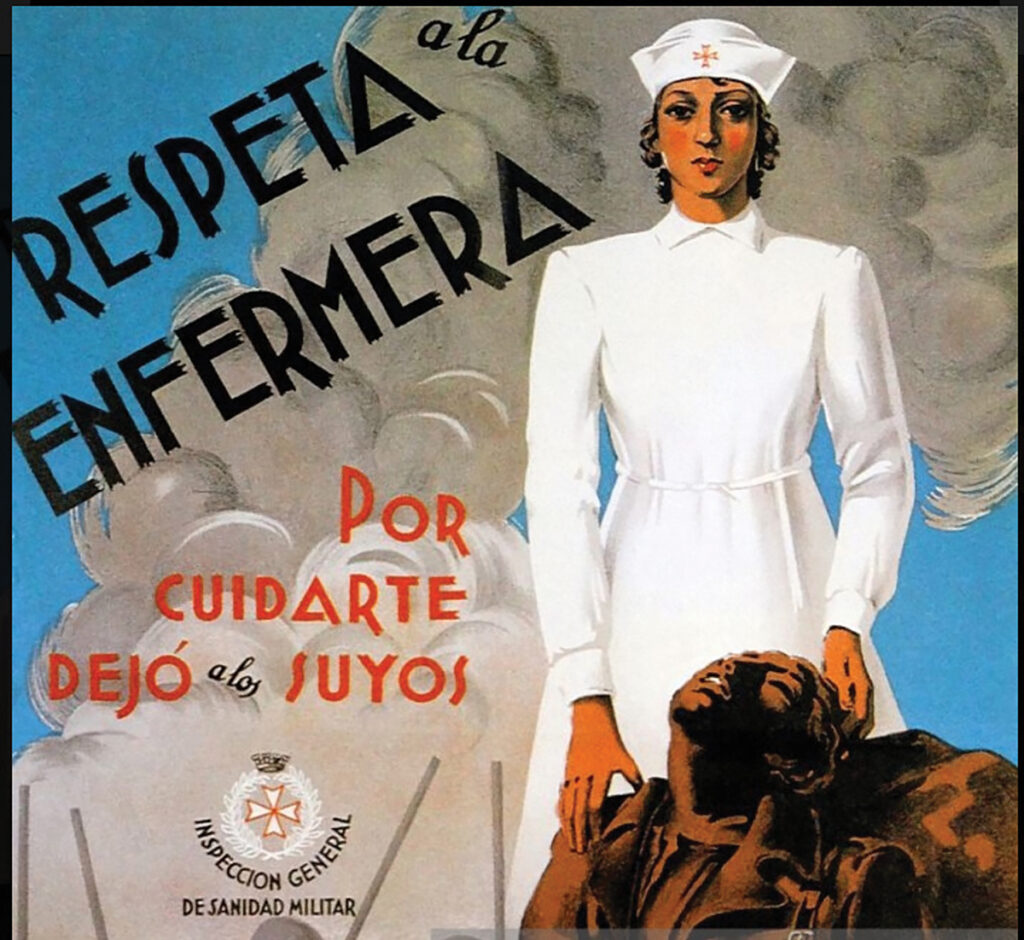

Other wars also produced dramatic poster art. During the Spanish Civil War, which was marked by horrifying violence against both combatants and civilians alike, the Spanish Republican Army’s inspector general of military health issued a 1938 poster (above) urging Spanish soldiers, “Respeta a la enfermera — por cuidarte dejó a los suyos” (“Respect the nurse — to care for you, she left her own”).

Spreading Awareness — And Calling for Vengeance

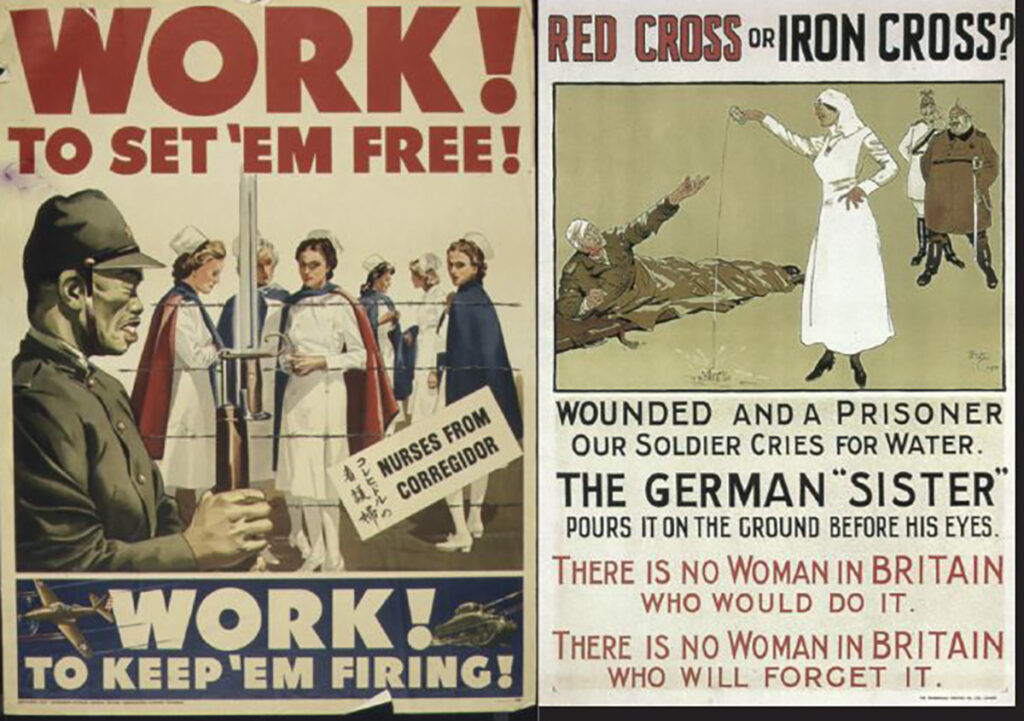

Wartime posters sometimes sought to remind civilians of the plight of nurses in uniform. For example, throughout WW2, posters circulated in the U.S. urged people on the home front to remember the 77 Army and Navy nurses captured by the Japanese Army on the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island in the Philippines in the spring of 1942.

Some of these posters, like a distinctive Office of War Information poster by a now unknown artist that today is part of the National Archives (bottom, left), featured racist caricatures of Japanese soldiers, a common feature of U.S. propaganda images from WWII. In times of war, posters sometimes called for vengeance as well as solidarity.

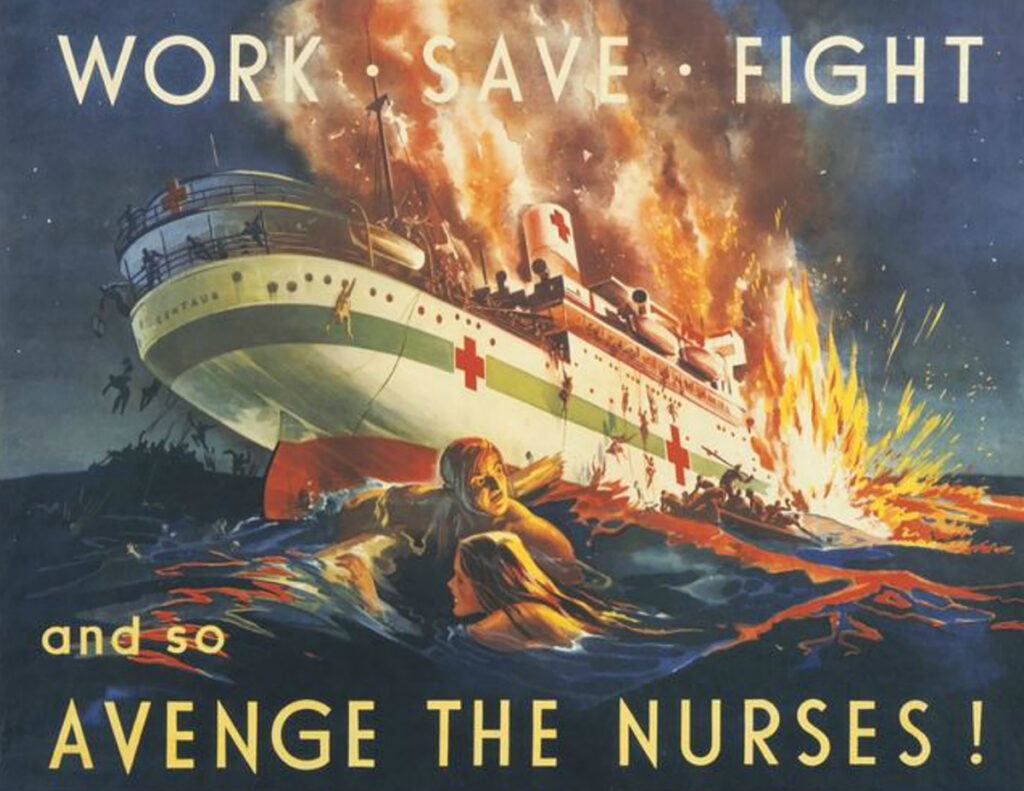

On May 14, 1943, a Japanese torpedo sank the clearly marked Australian hospital ship Centaur, claiming the lives of two-thirds of her passengers and crew. Only weeks later, artist Bob (Arthur) Whitmore created a vivid poster image (above) of the flaming, sinking hospital ship’s overfilled lifeboats and desperate passengers, based on the account of Sister Ellen Savage, the only one of the 12 nurses aboard the Centaur to survive the attack. These posters were broadly distributed in Australia and made nurses the center of the Commonwealth’s wartime messaging campaign.

While the grotesque depictions of Japanese soldiers seen during WWII are an extreme example, the wartime propaganda machine often worked feverishly to paint the enemy as evil and cruel. A 1917 British poster (bottom, right) by Irish artist David Wilson (credited to him and “WFB”), which now hangs in Britain’s Imperial War Museum, vilifies a German nurse, presenting her mistreating a British POW while German officers look on smiling.

Images of a Bygone Age

Modes of mass communication change as technology evolves. By the 1960s, when nurses were desperately needed for the Vietnam war effort, recruiters turned to other forms of media to get their message out. The striking posters that once covered the walls of public spaces gave way to radio and television commercials, and to magazine and newspaper advertising.

Although their styles and themes may be specific to a particular era, posters are part of a country’s cultural heritage. They are often reprinted in academic books and hung in museums. Here in the U.S., copies of the best and most significant posters reside in the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives, and the Library of Congress.

Wartime nursing posters from 100 years ago can seem like relics, and their racist and sexist depictions can be jarring to modern viewers. Yet, many of the messages are universal. Nurses responding compassionately and heroically in crisis is a theme that still endures and resonates today.

In this Article: Historical Nurses, Nurses at War