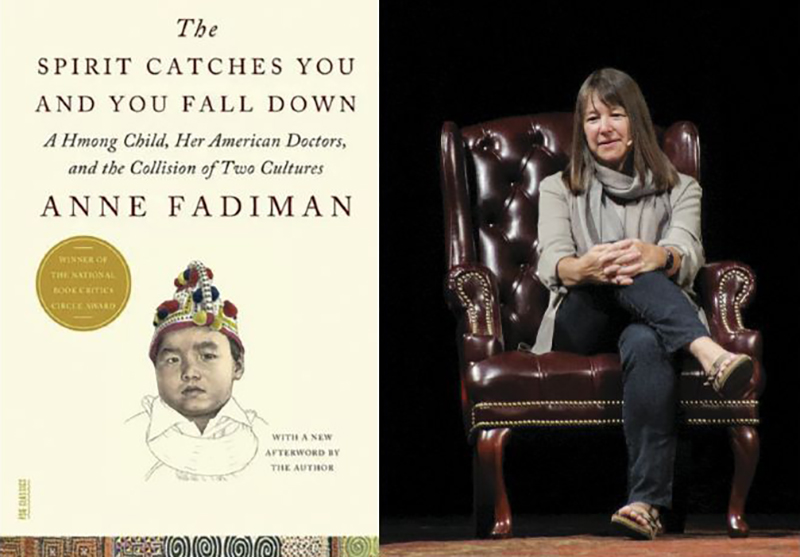

Nursing Book Club

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman

A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures

Back in 1997, Anne Fadiman wrote The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, documenting the experience of a Hmong family in Merced, Calif., 10 years earlier. The book, which won the National Book Critics Award, was a wake-up call on the need for cultural sensitivity in medicine.

During the Vietnam conflict, many Hmong people in Laos fought on the side of the United States. After the U.S. withdrawal in 1975, these Hmong-Lao fled Laos for Thailand, ending up in overcrowded refugee camps. Thousands emigrated to the U.S. in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, often settling in California.

As this book clearly documents, many faced a collision course with American culture.

Good and Bad Spirits

The subject of this book, Lia Lee, was born in 1982, the 14th child of Four and Nao Kao Lee, and the first to be born in the U.S. After her birth, her family found they were unable to bury the placenta beneath her birthplace, considered an inauspicious sign.

Hmong believe in spirits — both good and bad — and that your health depends on evading the bad spirits while capturing the good to stay within your body. The book’s title, “the spirit catches you and you fall down,” is a literal translation of the Hmong term quag dab ped, a condition we call epilepsy.

Lia suffered her first epileptic seizure when she was only 3 months old, after her sister slammed a door. In the Hmong belief system, quag dab ped is a special disease — acknowledged as serious, but also carrying some distinction. A person chosen for this illness is believed to have intuitive sympathy for other sick people, making them well-suited to becoming a txiv neeb, a traditional healer.