Feature

Shots in the Arm

A Day with a public health nurse at a COVID-19 vaccination clinic

As a public health nurse for the health department where I live in Bergen County, N.J., I wasn’t surprised to get a call one night in late December, informing me that our county’s first batch of 1,000 doses of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine would be arriving in two days.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy has established the phases and timeline for COVID-19 vaccination. The hope is that 75 percent of New Jersey’s nearly 9 million people will be vaccinated by late spring, an immunization campaign of a scale never before attempted here.

California has an even more daunting task — inoculating 40 million people!

Beyond a Flu Clinic

If you’ve ever participated in a flu clinic, you already have a good idea of the general procedures, but COVID-19 vaccination clinics involve some additional challenges.

Patients must preregister online (via our county website), which allows doses to be prepared according to the expected number of patients so that none are wasted. Unlike a flu shot clinic, we don’t let patients leave until they’ve been observed for reactions. (These COVID-19 vaccines are still subject to FDA emergency use authorization, so we have to watch carefully for any adverse effects.)

Also, the current COVID-19 vaccines each require two doses of the same vaccine type for full effectiveness, which demands additional patient education and follow-up.

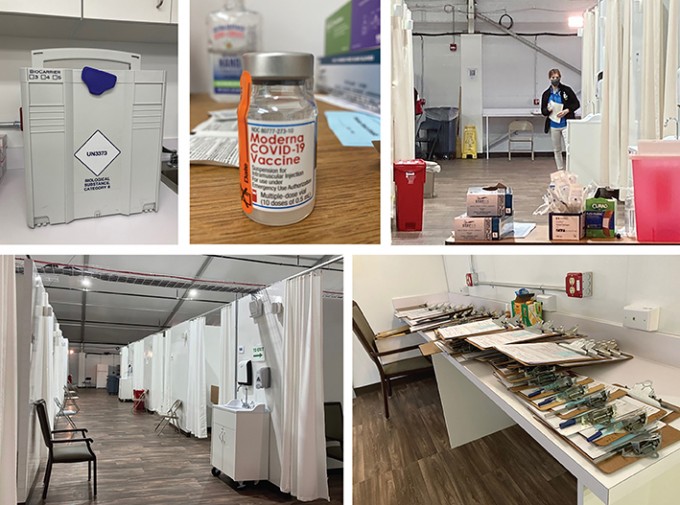

Logistics

Years ago, our county conducted a mock training program in response to a hypothetical accident at a nearby nuclear power plant.

In our scenario, the public health system had to quickly mobilize to provide residents with emergency iodine tablets at designated dispensaries. This endeavor required medical personnel to coordinate with emergency services and volunteers. I studied the Incident Command System in order to be aware of the levels of communication and to memorize important acronyms.

Participating in this mock exercise taught me a valuable lesson regarding what it takes to successfully run logistics for a mass event. A lot of it comes down to small details. For example, if you distribute flashlights you also need to supply batteries, and people who are asked to fill out forms need a pen and a hard surface to write on.

We set up our COVID-19 clinic In a self-contained field hospital, constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers in a parking lot of our large county hospital. It had been solidly built to hold 50 patients in five pods.

Each pod had an aisle with 10 curtained cubicles, five on each side, each with a bed, chair and bedside table. All were wired for electrical power and equipped with call bells. The hospital included restrooms, some with showers; a number of sinks; a medication room; and a break room with refrigerator and microwave.