Profiles In Nursing

Nursing in the Wild West

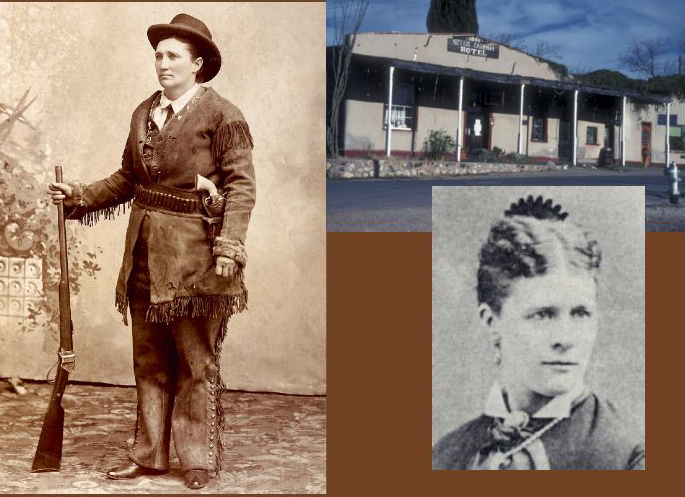

The true tales of Calamity Jane and Nellie Cashman

It may be difficult to believe today, but there was a time when nurses suffered a dubious reputation. While the nuns who founded nursing orders and hospitals were seen as ministering angels, lay nursing was seldom considered a respectable profession, and was sometimes practiced by some very colorful, rough-and-tumble individuals.

Here are the nursing stories of two such characters: Nellie Cashman and the legendary Martha Jane Cannary Burk, better known as Calamity Jane.

Martha “Calamity Jane” Cannary Burk (1852?–1903)

Hellion with a heart of gold

by Elizabeth Hanink, RN, BSN, PHN

Martha Jane Cannary Burk, better known as Calamity Jane, was a notorious frontierswoman, sharpshooter and Army scout. She took advantage of her childhood immunity to smallpox to care for stricken miners during an 1878 outbreak in Deadwood, S.D.

The Legend

Hard facts about the life of Calamity Jane aren’t easy to come by. Her fabrications (and the many legends that have grown up around her) have made it almost impossible to separate truth from fiction. Was she married to Wild Bill Hickok? Did she have his child? Did she have a child at all? No one really knows for sure.

Calamity Jane was probably born in Missouri around 1852. As a child, she survived an episode of smallpox that apparently left her immune to the disease. Her survival was perhaps the only good thing that occurred in her childhood, which featured frequent moves, the early deaths of her feckless parents, and her ensuing responsibility for (by some accounts) as many as six younger siblings.

With an upbringing like that, it’s no wonder that Calamity Jane developed into an unruly, undisciplined hellraiser who drank heavily and was usually penniless.

Heroine of the Plains

According to her 1896 autobiography The Life and Adventures of Calamity Jane as Told by Herself, she received her famous nickname from a Capt. Egan, a cavalry officer whose life she saved during an 1873 battle.

After Egan was shot, Calamity Jane rode to his rescue just in time to prevent him from falling off his horse. Afterward, Egan dubbed her “Calamity Jane, the heroine of the plains.”

As with many of Calamity’s anecdotes, there is no real evidence as to whether this actually happened or not, but it makes for a good story.

Whatever her faults, it’s generally agreed that Calamity Jane was kind, attentive and willing to nurse anyone — not a bad recommendation. Several accounts report her nursing the sick during various typhoid eruptions and a black diphtheria outbreak in Green River, Wyo.

However, her greatest nursing-related fame followed the deadly 1878 outbreak of smallpox in Deadwood, S.D.

The Smallpox Menace

Medicine on the frontier was spotty at best. Most doctors were uneducated and poorly equipped. The most common tools in the doctor’s kit were calomel (a laxative that could destroy teeth and gums), castor oil and a variety of popular patent medicines consisting mostly of alcohol and/or narcotics like cocaine. Nurses were whoever would do the work.

Few scientists and even fewer doctors in those days understood microorganisms, refrigeration, sterilization or antiseptics. Infectious disease could easily take hold in populations already weakened by grinding poverty and bad nutrition. Surviving a serious injury or illness depended as much on luck as anything else.