Profiles In Nursing

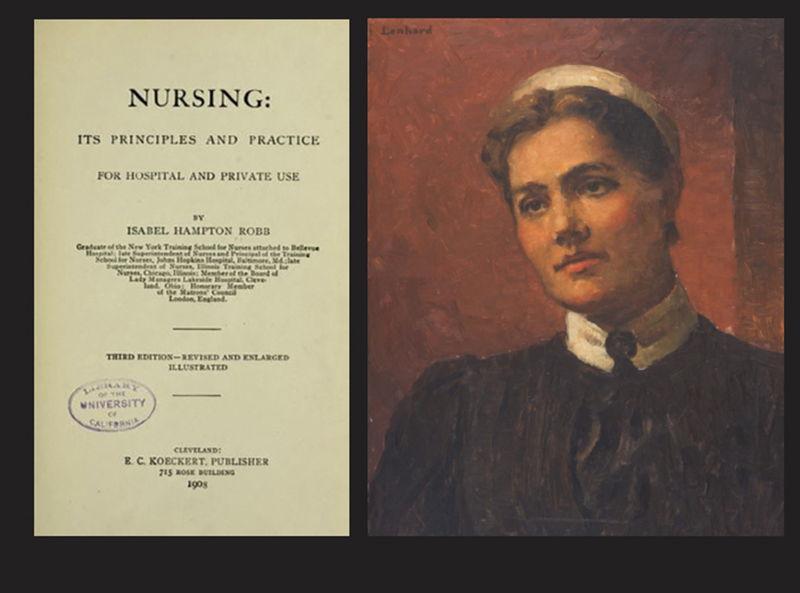

Isabel Hampton Robb (1859–1910), Founding President of the ANA

She brought rigor and standards to nursing education

The first president of what is now the American Nurses Association (ANA), Isabel Adams Hampton Robb was also an important innovator in American nursing education. She spearheaded a movement to transform nursing schools from hospital training programs into rigorous academic institutions, helping to make nursing the profession it is today.

From Schoolteacher to Nurse

Isabel Hampton was born in 1859 in Welland, Canada. At the age of 17, she became a school teacher at an annual salary of $300. One afternoon four years later, Hampton overheard her principal discussing a hospital in New York that was accepting nursing school applicants. A few of her teaching colleagues considered applying, but only Hampton took the chance.

She was accepted into the Bellevue Training School for Nurses, one of the first schools in the U.S. to be based on the theories of Florence Nightingale. After graduation, Hampton spent about 18 months in Italy with St. Paul’s House for Trained Nurses in Rome.

First Role in Nursing Leadership

Despite having a mere three years of nursing experience, Hampton became superintendent of the Illinois Training School for Nurses at Cook County Hospital in Chicago.

From the moment of her arrival, she had ambitious ideas on how to improve nursing education. Up to that time, a nursing student’s training was based solely on the needs and capacity of the hospital the school was affiliated with, which could vary greatly. As Hampton later noted, the title of nurse could mean “anything, everything, or next to nothing,” depending on the individual’s training.