Feature

In Country: U.S. Nurses During the Vietnam War

Young recruits were promised romance and adventure. The reality was far different.

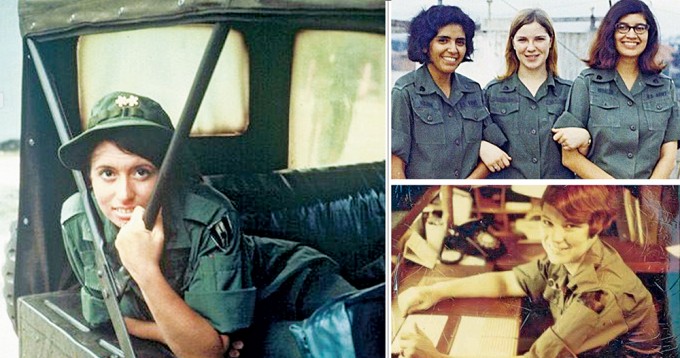

The nurses who served in the Vietnam War are among the least recognized of American military veterans. Many films and TV programs about U.S. involvement in Vietnam do not depict a single American nurse.

In fact, more than 6,000 U.S. nurses — the large majority of them women — served in Vietnam during the war. Some didn’t make it home alive, and many others were changed forever.

Recruiting Nurses: Operation Nightingale

Although some American forces were stationed in Vietnam in the ‘50s, U.S. involvement in the region escalated dramatically in the 1960s. Between 1963 and 1969, the total number of U.S. military personnel in Vietnam grew from 16,000 to around 550,000, although until 1965, American troops were still officially considered advisers to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

As early as 1962, the buildup in Vietnam highlighted the urgent need for more military nurses. The civilian healthcare sector was struggling with nationwide nursing shortages, and both the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) and Navy Nurse Corps had shrunk to a fraction of their World War 2 strength.

Facing a shortfall of more than 2,000 nurses, the Army launched an ambitious recruitment campaign called Operation Nightingale. Recruiters targeted high schools, colleges and career fairs; ran newspaper articles; aired radio and television commercials; and assigned existing Army nurses to work as recruitment counselors.

The Lure of Romance

The nurse recruitment ads of this era were a world away from the images of chaos and brutality that would soon fill Americans’ evening news broadcasts, instead focusing on the opportunity, adventure and romance that supposedly awaited nurses in the U.S. Army.

During World War 2, military regulations had expressly forbidden nurses to marry while in service. Now, Army recruiting ads actually emphasized dating and romance.

One 1964 ad showed an attractive, well-scrubbed nurse at work and out on the town, emphasizing that “modern nursing’s most stimulating jobs” also included “the fine social life that is part of being an Army officer.”

Another Army brochure actually declared, “Don’t be surprised if a diamond crops up on your left hand!”

As the war escalated, some ads appealed to nurses’ patriotism, but glamour and empowerment remained central recruiting messages. “Today’s Army Nurse can do more,” proclaimed a 1969 ad. “Heading up her own staff. Making her own decisions. Specializing in the field of her choice.”

Average Age: 23

Most Vietnam-era military nurses were in the Army, with smaller numbers serving in the Navy Nurse Corps and a handful in the Air Force. The average age was 23, but some nurses were as young as 20 and a few were in their 40s. Many nurses were recruited directly out of nursing school. Only 35 percent had two or more years of nursing experience when they were commissioned.

While nurse recruitment efforts were often aimed at women, about 20 percent of the military nurses who served in Vietnam were men. The Army Nurse Corps had accepted men since 1955, while the Navy Nurse Corps commissioned its first male nurses in 1965.

A few male nurses who served in Vietnam were draftees, part of a mostly unsuccessful effort to fill ongoing shortages. Although there were proposals to draft female nurses, they were never implemented.

“I Wanted to See More of the World”

Nurses’ motivations for joining the military were as diverse as the nurses themselves. Some joined to satisfy a sense of adventure.

“I didn’t join for a noble cause or thinking I could change the world, I just wanted to see some of the world, like Germany, Japan or England,” says former 1st Lt. Louise “Lou” Eisenbrand, RN, who was an ER nurse at the Army’s 91st Evacuation Hospital at Chu Lai in 1969–70.

As today, some nurses joined for financial reasons.

“They had something called the Army Student Nurse Program, through which you could have your last year or two paid for,” explains Phyllis Breen Cogan, who was stationed at Chu Lai’s 27th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital from 1969 to 1970.

“Six months before I graduated, I was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps, and they paid for my last year of school. It was wonderful.” Cogan eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Some nurses were driven by a desire to help, even if they disapproved of the war. “I thought, ‘I have got to go over there and try to stop this war and stop the hurting,’” says Marj Graves, RN, who was stationed at the Army’s 24th Evacuation Hospital in Long Binh in 1971–72 and rose to the rank of captain.

“Why I ever thought that I would be able to have any impact on the war that way was … way out in left field. But, I knew I could make a difference nursing-wise, and so I volunteered to go.”

Not all the nurses who joined expected to serve in a combat zone. Military recruiters sometimes led nurses to believe that only those women who volunteered would be sent to Vietnam — which made for a rude surprise upon receiving orders to ship out. Some nurses who saw active duty during the war were never stationed in Vietnam, serving instead aboard Navy hospital ships or at U.S. military bases elsewhere in Asia.

Too Hot and Humid for Nylons

Nurses arriving in Vietnam quickly found that the climate didn’t lend itself to the glamour the recruitment posters had promised. Vietnam was miserably hot and humid, which made the nylon stockings required with the white nurse’s uniform very uncomfortable. In practice, Army nurses usually wore fatigues, despite frequent complaints that they weren’t feminine enough for women.

When they arrived, nurses were assigned to their housing units. A dozen Army nurses typically shared each unit. The units, nicknamed “hootches,” each had a shower, a small kitchen and just enough room for nurses to have a few shelves as well as their footlockers.

The hootches also had rats, bugs and frequent problems with mold and mildew.

Civilian Vietnamese women were hired to handle laundry and housekeeping. Some bases even hired local civilians to operate on-base beauty parlors so that female personnel could keep their hair in some kind of order.

Dealing with Vietnamese civilians was complicated by the fact that few American nurses spoke the language. There was also no guarantee that even a seemingly friendly and sympathetic local wasn’t a Viet Cong agent or sympathizer.

“Incoming!”

Nurses were noncombatants, but that didn’t necessarily mean they were safe. New arrivals quickly noticed that military buses had black chicken wire over the windows to keep out grenades and shrapnel. A green nurse who tried to open a bus window for relief from the heat was quickly warned that the windows had to remain closed for the occupants’ own protection.

Unlucky nurses could fall victim to bombings, ambushes or booby traps — the Viet Cong regarded American military personnel as invaders and dealt with them accordingly. Rocket and mortar attacks were another danger.

The only American nurse killed by enemy fire during the war, 1st Lt. Sharon Lane, RN, died in a rocket attack on June 8, 1969. (Seven other American nurses died of injuries or illness during the war, but no others were killed by enemy action.)

In-Country Status

Nurses’ tours in Vietnam lasted for one year, although a few returned for two or more tours. An individual’s status depended on the amount of time spent in-country. A nurse who had been in Vietnam for six months had more credibility than a doctor who had just arrived, even if that doctor was very experienced in the States.

It was not simply about pecking order; personnel who had been in Vietnam longer were better-adjusted to the environment and the stress and danger it entailed.

A Blessing and a Curse

Military service had both advantages and pitfalls for nurses. On the plus side, nurses enjoyed far greater authority and autonomy than in any civilian setting. At home, nurses were expected to be subservient to physicians and were still often saddled with menial chores. Most military nurses were commissioned officers, supervising enlisted corpsmen and orderlies and sometimes acting as department heads.

Particularly in an emergency, an Army or Navy nurse in Vietnam might be allowed (or even required) to perform procedures well beyond their normal scope of practice. Unfortunately, that autonomy and responsibility didn’t erase gendered expectations. Military officials and many servicemembers expected female nurses to be attractive as well as nurturing, arguing that sex appeal and femininity were important for morale.

For female nurses, being constantly surrounded by men could also be both a blessing and a curse. As the recruiting ads had said, women in uniform seldom lacked for male attention, whether welcome or not. Some women met and married their husbands in Vietnam, while others enjoyed having their pick of available men in a freewheeling environment.

However, sexual harassment was a constant problem. So was sexual assault, which added another layer to the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that many nurse veterans brought home with them.

“Whoop, Whoop, Whoop”

An Army documentary filmed during the war (which you can find on YouTube) shows nurses shopping, reading, visiting the hair salon, writing letters, playing with civilian orphans and training the Vietnamese Women’s Army Corps in their spare time.

While that was all true so far as it went, the footage paints a deceptively tranquil picture that does not capture the mental stress of military nursing.

Every person who ever worked or lived on a medical base became conditioned to feel a rush of adrenaline at the distinctive “whoop, whoop, whoop” sound of an approaching helicopter.

The use of helicopters allowed wounded soldiers or Marines to reach hospitals much faster than in previous wars. Medevac choppers often picked up, unloaded and took off again without ever stopping the rotating blades.

Gruesome Injuries

Such speedy medical evacuation significantly improved the odds of surviving even severe wounds. The number of American personnel wounded in combat during the Vietnam War outnumbered those killed in action by more than six to one.

However, the injuries the nurses saw were if anything more horrible than ever, thanks to widespread use of weapons like assault rifles and rocket-propelled grenades. Many wounded soldiers became amputees and some were left paralyzed.

Improvised weapons and booby traps presented some unique hazards. “The enemy became very crafty,” recalls Diane Carlson Evans, an Army Nurse Corps first lieutenant who remained with the Corps for five years after returning from Vietnam and later became a leading advocate for female Vietnam veterans. “They would lace punji sticks with human feces. A soldier would step on it: instant injury and certain infection.”

Emotional Triage

Many of the soldiers, Marines and sailors the nurses treated were very young: 18 to 22 years old, with a few as young as 17. Most of the nurses weren’t much older than their patients, and few were prepared for what they witnessed.

“I had no experience in emergency room, no trauma or intensive care training,” recalls Marsha Four, RN, a former ANC first lieutenant. “I was a totally, totally green nurse. To say ‘challenging’ doesn’t come close to the feelings that I had about being incompetent. Their lives were in my hands.”

The emotional demands on the nurses were substantial.

“We didn’t just take care of their physical wounds, any nurse that has served in any war zone will tell you,” says Grace Lilleg Moore, who was a second lieutenant at the Army’s 12th Evacuation Hospital in Cu Chi in 1968–69. “We were their emotional support. We were their mother, their wife, their girlfriend.”

Nurses also treated prisoners of war and civilians, including women and children brought to American hospitals for treatment. The war took a heavy toll on the Vietnamese population. Today, the government of Vietnam estimates that the total civilian death toll was about 2 million.

“One of the worst memories of Vietnam was seeing children die,” says Mary Beth Crowley, an ANC second lieutenant from 1969 to 1971. “Every time somebody died, I died with them.”

“I Don’t Think I Ever Slept in Vietnam”

Military nurses usually worked 12-hour shifts six days in a row, but if many casualties came in, a 12-hour shift could easily become 24 or even 36 hours. “I don’t think I ever slept in Vietnam,” Evans says. “I think I was always on the verge of sleeping, waiting for that call and choppers overhead.”

Nurses sometimes found novel ways of blowing off steam between shifts. Lou Eisenbrand and her colleagues at Chu Lai took up waterskiing. “We used a Jeep to pull the boat, but I have no idea where the Jeep and boat and skis came from,” she says.

Dealing every day with horror presented some nurses with a crisis of faith.

Moore recalls thinking, “I’m done with you, God. My God wouldn’t do this to these boys.” Others found themselves becoming callous or just numb. In the 1987 book Nurses in Vietnam: The Forgotten Veterans, former Army nurse Jacqueline Navarra Rhoads recalls this gruesome anecdote:

I remember this nurse came in and she was scheduled to take the place of another nurse. When she saw me, I went to greet her and I had this leg under my arm. She collapsed on the ground in a dead faint. I thought, “What could possibly be wrong with her?” There I was trying to figure out what’s wrong with her, not realizing that here I had this leg with a combat boot still on and half the man’s combat fatigue still on, blood dripping over the exposed end. And I had no idea this might bother her.

Different nurses found different strategies for coping with the burdens of war. Some did their best to compartmentalize, pushing the horrors out of their minds. Some drank or turned to drugs, problems that sometimes followed them home.

Female Vets Not Welcome

While many who served in Vietnam longed for home, the return wasn’t always easy. Some nurses missed the strong bond they’d formed with their comrades, which they rarely found again. Nurses who went to work in civilian hospitals after the war were often frustrated by the limitations of their jobs. Others found themselves missing the intensity of their wartime experience.

Many never spoke of their experiences in Vietnam, which deepened their postwar stress and depression. Some developed symptoms of what is now identified as PTSD.

Veterans’ organizations weren’t always welcoming of women who’d served.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars didn’t accept female veterans until 1978, Vietnam Veterans of America not until several years after that. Even the Veterans Administration was ill-equipped to meet the needs of female Vietnam vets.

A Memorial in Washington

A vigorous advocacy campaign led by nurses and former nurses eventually brought about some much-need improvements.

In 1984, Diane Evans founded the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project (VWMP), originally called the Vietnam Nurses Memorial Project.

After a nine-year struggle, the memorial — a 15-foot bronze statue designed by sculptor Glenna Goodacre — was dedicated on the Mall in Washington, D.C., near the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (whose designer, Maya Lin, had opposed the monument).

Today, the statue is a popular tourist destination and a reminder of these often-forgotten veterans.

LORILEA JOHNSON, RN, MSN, FNP-BC, is a family nurse practitioner who has worked in urgent care for the past 20 years. She is currently completing her doctorate in nursing at Missouri State University.

In this Article: Historical Nurses, Nurses at War, Vietnam War