Profiles In Nursing

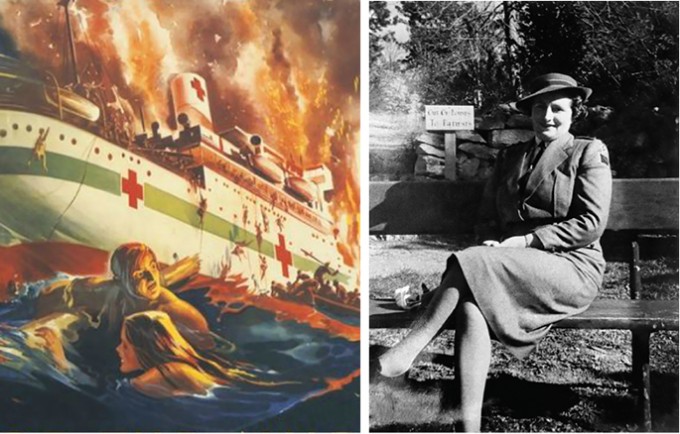

Ellen Savage (1912-1985), Australian Nurse Who Rallied a Nation at War

She survived the sinking of a hospital ship during WW2

Even if you practice for decades, your entire career may be defined by only a few moments. For Australia’s Ellen Savage, it was the three minutes it took for the Australian hospital ship Centaur to sink in 1943.

Australian Army Nurse

Ellen Savage grew up in Quirindi, New South Wales, and received her nursing training at New South Wales’ Newcastle Public Hospital. She spent her free time swimming and surfing, skills that would later prove invaluable.

During the late 1930s, Savage continued her education, becoming what Australia called a “triple-certificate” nurse, with diplomas in general nursing, midwifery and mothercraft. She then went to work at the Baby Health Centre in Tamworth before joining the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in May 1941.

That November, she was reassigned to the Second Australian Imperial Force, the expeditionary branch of Australia’s military forces, and embarked aboard the hospital ship Oranje. One of Savage’s three daughters also became a hospital ship nurse.

Aboard the Centaur

Built in 1924 for Great Britain’s Blue Funnel merchant line, AHS Centaur spent much of her life carrying passengers, cattle and sheep between West Australia, Singapore and Malaysia. Pressed into military service in 1941, she became known as a lucky ship for her good fortune in evading Japanese bombs.

The Australian military converted the 3,222-ton freighter into a hospital ship in early 1943. Around the same time, Savage received a commission as a lieutenant and was assigned to Centaur’s 12-member nursing staff.

In May, Centaur set sail for Port Moresby, New Guinea, to pick up wounded Australian soldiers. In compliance with international treaty requirements, the ship wore prominent red crosses and was brightly lit, sailing without escort.

Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, she was supposed to be off-limits to attack. Unfortunately for her 332 officers, crew and medical personnel, Japan was not then a signatory of the Geneva Convention. At 4:10 a.m. on Friday, May 14, submarine I-177 of the Imperial Japanese Navy torpedoed the Centaur, sending her to the bottom in a mere three minutes.