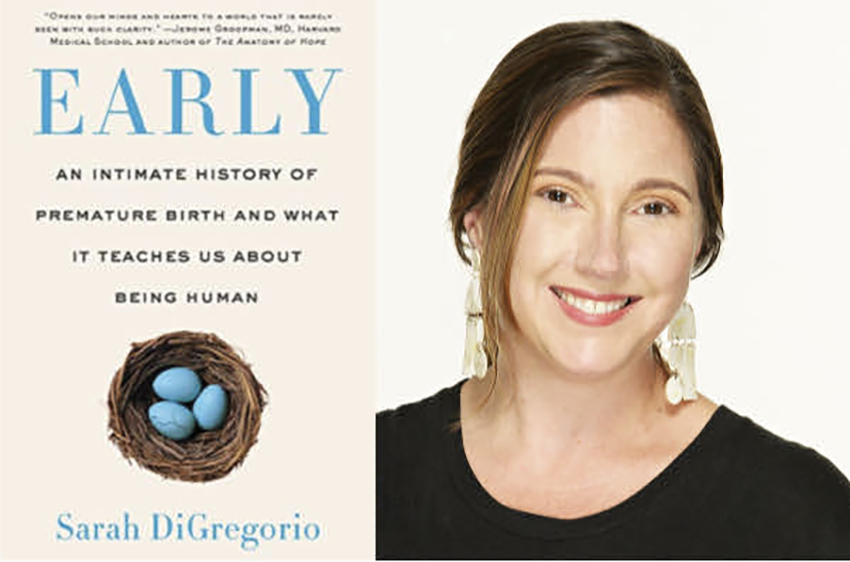

Nursing Book Club

Early by Sarah DiGregorio

An Intimate History of Premature Birth and What It Teaches Us About Being Human

Delivering a baby at 27 weeks led journalist Sarah DiGregorio to write a well-researched book about prematurity, from the causes to treatment options to the hard choices facing parents and the healthcare team.

Sarah DiGregorio’s daughter Mira began to fall off the growth curve while still intrauterine, at 24 weeks. Testing showed that DiGregorio had a subpar placenta, so her obstetrician decided to prepare her for delivery at just 27 weeks — very premature. (If you’ve never had a child or worked in L&D, a full-term baby is 37–42 weeks.)

Prematurity From Many Angles

Little Mira was unready for life outside the womb, weighing just 1 pound, 13 ounces at birth. As DiGregorio remarks, “She was your average one-and-a-half-pound baby whose heart stopped several times a day, who needed blood transfusions to stay alive, who needed life support to breathe, eat, and stay warm.”

In the prologue of journalist DiGregorio’s recent book Early, we learn about Mira’s postnatal care (which is also a reminder of the importance of the nurses in the NICU). She describes what it feels like to be discharged without the baby to whom she’s been so intimately attached for the past many months. DiGregorio was not able to take her daughter home until Mira’s weight reached 4 pounds, which took 59 days in the hospital.