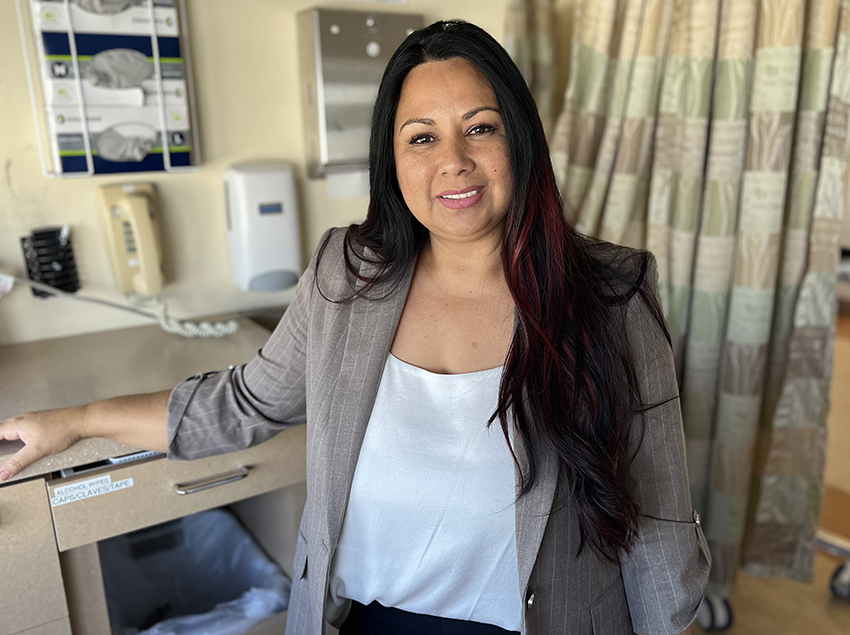

Profiles In Nursing

Dolores “Dee” O’Hara (1935–), First NASA Space Nurse

Her nursing skills launched an out-of-this-world career

When Dolores “Dee” O’Hara entered nursing school after graduating from Oregon’s Lebanon High School in 1953, she had no idea her nursing career would have her literally reaching for the stars. In 1960, she became the first nurse to join NASA, launching a new specialty: aerospace nursing.

Surprise Landings

Born in Nampa, Idaho, O’Hara grew up in Oregon. After being impressed by a nurse at her high school’s career day, she enrolled in the Providence Hospital School of Nursing and later became a surgical nurse at the University of Oregon Medical School.

While she enjoyed bedside nursing, the physical toll exacerbated O’Hara’s back problems, so she pivoted to diagnostic roles, including lab testing and radiology.

In the spring of 1959, her life took another unexpected turn when her roommate suggested they both join the Air Force. O’Hara’s first reaction was skepticism — “Nice girls don’t do that,” she declared — but the allure of traveling and seeing the world ultimately changed her mind.

After completing officer training, O’Hara departed for her first assignment, in the labor & delivery unit of the Patrick Air Force Base hospital in Cape Canaveral, Fla.

An Out-of-This-World Offer

In November 1959, O’Hara was summoned to the office of the hospital commander, Col. George M. Knauf, who offered her a remarkable opportunity: to join Project Mercury, a new NASA program to put human astronauts into space.

O’Hara had no idea what an astronaut was, and she had never even heard of NASA (which had been established just 13 months earlier), but she accepted the job offer, “not knowing at all what I had committed myself to.”