Profiles In Nursing

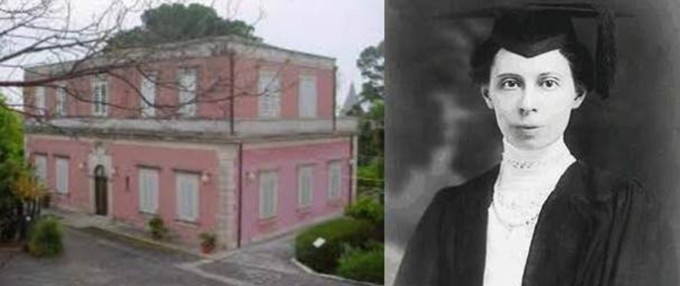

Christiane Reimann (1888-1979) and the International Council of Nurses

This headstrong heiress was a realistic visionary

A quick review of nursing history reveals that many of our forebears were formidable personalities. No one liked to cross Florence Nightingale or Dorothea Dix, and the same could certainly be said of Christiane Reimann. Descriptions of her range from “uncompromising” to “always ready to give her opinion.”

Yet, Reimann led an international nursing organization through some of its most contentious times — and later left a substantial fortune that established what’s often referred to as “the Nobel Prize for nursing.”

“A Nurse Is Not a Lady”

Her single-mindedness first manifested itself in a big way when Reimann, the daughter of an affluent family in Copenhagen, Denmark, first became a nurse despite strong family opposition. “When I decided to become a nurse, my parents were distraught,” she later recalled. “My uncle would not even shake hands with me, declaring ‘a nurse is not a lady.’ ”

Not to be deterred, Reimann completed her training at Bispebjerg Hospital in 1916. At the end of World War I in 1918, she sailed on the first postwar ship from Copenhagen to New York, dodging leftover naval mines and icebergs the whole way.

By 1925, she had obtained both her bachelor’s degree and her master’s degree in nursing from Teachers College, Columbia University, making her the first ever graduate-prepared Danish nurse. Her studies brought her into contact with many contemporary American nursing leaders, including educators Mary Adelaide Nutting and Isabel Maitland Stewart, then members of the Teachers College nursing faculty.

Joining the ICN

Reimann also joined the International Council of Nurses (ICN), realizing that despite their great disparities, nurses around the world needed to be united.