Feature

Black Nurses and the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic

A tale of a deadly outbreak, inflammatory propaganda and heroism

In 1793, Philadelphia was as large and as cosmopolitan a city as could be found in the new United States. Until 1800, Philadelphia served as the U.S. capital. The city was also home to a substantial number of people of color. Many were freedmen and some were prosperous.

Philadelphia’s white residents often regarded their Black neighbors with disdain and hostility, made worse by an influx of French refugees from Haiti and Santo Domingo, where there had been recent slave uprisings. (At the time, many prominent officials were slave owners, including then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson.)

With so much tension, it would not have taken much to cause an explosion. The yellow fever outbreak that summer was more than sufficient.

A Cry for Help

As the disease spread, so too did panic. Some 20,000 residents fled the city. Deaths became so frequent that the College of Physicians asked city officials to stop tolling bells for the dead because the constant ringing was so oppressive.

At the time, no one knew what caused the outbreak. (It was not until the 1880s that the Aedes aegypti mosquito was identified as the principal transmission vector of yellow fever.) Many Philadelphians believed the outbreak was somehow linked to “bad vapors” from coffee left rotting on the docks.

Most people knew the disease was contagious, although many wrongly believed Black people were immune. With the exodus of so many able-bodied residents, care for the sick and dying was limited at best. In desperation, civic leaders — including Declaration of Independence signatory Benjamin Rush, M.D., then a professor at the Institutes of Medicine — approached the city’s Black community for help.

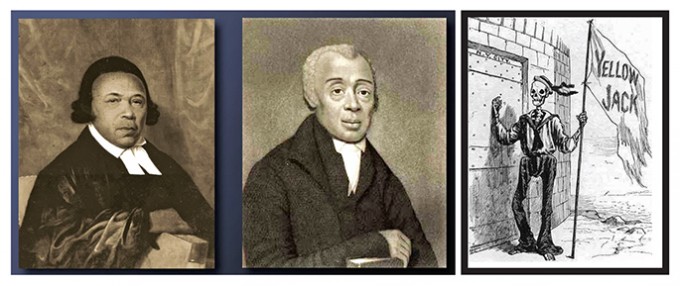

The leaders of Philadelphia’s Free African Society, a mutual aid organization founded in 1787 by ministers Absalom Jones and Richard Allen in partnership with Black abolitionists like William Gray, willingly agreed to provide that assistance.

Few of the Black Philadelphians who answered the call had any medical training. Nursing, Jones and Allen later remarked, “is in itself a considerable art, derived from experience as well as the exercise of the finer feelings of humanity — this experience, nine-tenths of those employed, it is probable, were wholly strangers to.”

Skilled nurses were in very short supply in Philadelphia, and some had already balked at the horrendous conditions at the makeshift hospital established in Andrew Hamilton’s Bush Hill mansion. (Jones and Allen noted that Bush Hill’s two Black nurses were among the few who stayed.)

As the epidemic worsened, greater responsibility fell on the Black volunteers. After several physicians died of the disease, Rush even recruited Jones and Allen, who had some medical experience, to act as nurses.

“[He] directed us where to procure medicine duly prepared, with proper directions how to administer them, and at what stages of the disorder to bleed [the patients]; and when we found ourselves uncapable of judging what was proper to be done, to apply to him,” the two ministers later wrote.

By their own account, they cared for “upwards of 800 people,” asking little or nothing in return.

No Good Deed Unpunished

Unfortunately, prejudices die hard, and there’s nothing like a pandemic to bring them out. That November, a prominent white printer, Mathew Carey, published an inflammatory pamphlet with the cumbersome title A Short Account of the Malignant Fever Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia with a Statement of the Proceedings That Took Place on the Subject in the Different Parts of the United States.

The pamphlet lambasted the city’s response to the epidemic. Carey directed much of his vitriol at the Black community. “The great demand for nurses … was eagerly seized by some of the vilest of the blacks,” he claimed. “They extorted two, three, four and even five dollars a night for such attendance, as would have been well paid by a single dollar. Some of them were even detected in plundering the houses of the sick.”

Striking Back

His charges did not go unanswered. Although he had not attacked them personally, Jones and Allen took exception to Carey’s vilification of their community.

The two Black ministers fired back in January 1794 with their own expansively titled publication, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year of 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications.

In their rebuttal, the ministers praised the Black nurses for their selfless work. Jones and Allen acknowledged that during the worst of the outbreak, desperate patients and families had sometimes offered or been asked for “extravagant prices” for any help.

However, the ministers noted that “there were as many white as Black people detected in pilfering, although the number of the latter employed as nurses was 20 times as great as the former.”

As for themselves, Jones and Allen explained, “At first we made no charge, but left it to those we served in removing their dead to give us what they thought fit.”

They added that the money they had received, which totaled some £233, 10 shillings and 4 pence, was well short of their expenses, which included hundreds of coffins for the dead and more than nine weeks’ wages for the five men they had hired to help them. The ministers took no wages for their own labor and published a complete tally of their receipts and expenses.

“Had Mr. Carey been solicited to such an undertaking, for hire,” Jones and Allen wrote, “What would he have demanded?”

Scenes of Horror

Jones and Allen presented a vivid picture of the nurses’ experience during the outbreak. Yellow fever causes delirium, which left some patients “raging and frightful to behold.” Others were “vomiting blood and screaming enough to chill [bystanders] with horror.”

The scene at the Bush Hill hospital was, in Carey’s own words, “as wretched a picture of human misery as ever existed. … The dying and the dead were indiscriminately mingled together.”

In these ghastly conditions, Jones and Allen write, the volunteer nurses worked “for a week or 10 days, left to do the best they could without any sufficient rest, many of them having some of their dearest connections sick at the time, and suffering for want.”

It was risky work, despite the myth of Black immunity. “When the people of colour had the sickness and died, we were … told it was not with the prevailing sickness, until it became too notorious to be denied,” the ministers recalled. “Thus were our services extorted at the peril of our lives.”

Despite their indignation at Carey — who had actually fled the city during part of the epidemic, something he’d sharply criticized others for doing — Jones and Allen were rightly proud of what their community had accomplished.

“Truly our task was hard, yet through mercy, we were able to go on,” they wrote. “We feel great satisfaction in believing that we have been useful to the sick and thus publicly thank Doctor Rush for enabling us to be so.”

You can read both pamphlets in their entirety and learn more about this extraordinary episode in Black history in the digital collection of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

The Scourge of “Yellow Jack”

by Aaron Severson

Yellow fever is a virulent mosquito-borne viral infection that plagued North America well into the 20th century. The disease’s name refers to the symptoms accompanying severe cases, which can include bleeding, vomiting and organ failure as well as fever and jaundice. English speakers often called the disease “yellow jack,” after the yellow quarantine flag flown during outbreaks.

About 85 percent of yellow fever cases are relatively mild, resolving within about a week. Severe cases, however, are extremely deadly, with case-fatality rates of up to 60 percent even today. Even more frighteningly, severe cases typically begin as mild ones that suddenly worsen after the patient begins to feel better.

Although yellow fever outbreaks usually coincide with mosquito season, it wasn’t until 1881 that Cuban physician Carlos Finlay, M.D., first hypothesized that the insects could transmit the disease.

Maj. Walter Reed, M.D., a U.S. Army surgeon, confirmed that theory through human trials in 1900. However, the virus wasn’t isolated until the late 1920s, and it took decades to develop an effective vaccine. Yellow fever remains a serious threat in many tropical areas of the Americas and Africa.

ELIZABETH HANINK, RN, BSN, PHN is a Working Nurse staff writer with extensive hospital and community-based nursing experience.

In this Article: historical epidemics, Historical Nurses, Public Health