Feature

Algorithms at the Bedside

Nurses, artificial intelligence, and machine learning

Every morning, the nurses in the Heart Rhythm Center at Cedars-Sinai’s Smidt Heart Institute take shift reports from a partner that isn’t human: a cardiac monitoring system powered by artificial intelligence (AI).

The AI’s morning report is based on heart rhythm data gathered during the night through patients’ implanted pacemakers and defibrillators.

While electrical devices for cardiac pacing and rhythm control are not new, the way the data are collected and examined is.

Using remote monitoring and machine learning systems that continuously analyze each patient’s heart rhythm, the machine automatically flags possible life-threatening abnormalities.

Useful, but Not Perfect

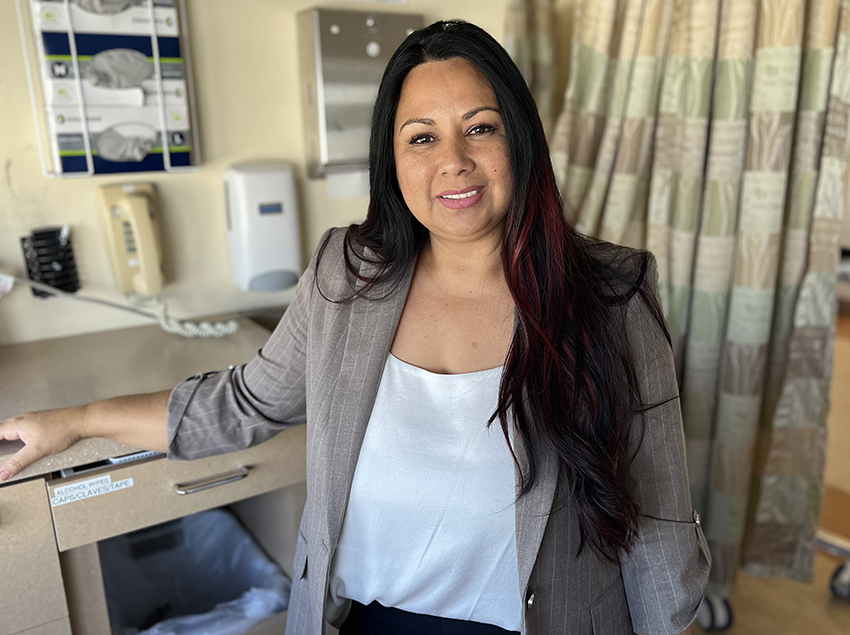

Hyun Joo Lee, RN, BSN, MBA, clinical operations manager of the Smidt Heart Institute, says the nurses who work with this technology regard the AI monitoring system as a valuable aide. She emphasizes that it is not a replacement for human clinical judgment.

“The AI algorithm is not perfect,” Lee explains. If the AI flags something, she says, “it could be what we call ‘noise’ or other factors, so our job is to do the first screening. If the machine states that the patient has atrial fibrillation (AF), the nurse has to look at it and ask, ‘Is it truly AF, or is it just noise?’ Our role is very important.”

The nurses at the Heart Rhythm Center are all highly trained certified cardiac device specialists, but as healthcare AI becomes more common, checking the machine’s work like this may become part of the daily routine for many nurses.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

“AI is fancy math,” says Karl Haviland, chief technology officer for the AI company Nearly Human. “The computer is really good at taking large sets of information in a way that a person isn’t.”

The types of AI now used in healthcare are machine learning (ML) algorithms: mathematical models that can be “trained” to recognize numbers, text and even images. Algorithms like these can learn to detect aberrations or the lack thereof, which makes them well-suited for time-consuming tasks like reviewing EKG data.

“Fast physicians can read maybe 100 EKGs per day, depending on how busy they are,” notes Lee. “The machine can now read 100,000 EKGs in one hour.” (She adds that it is still important for physicians to validate the machine’s findings.)

Stephanie Frisch, RN, MSN, Ph.D., a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine who was first introduced to AI in the emergency department about seven years ago, has seen firsthand how use of these models can help to improve care.

“Machine learning has the potential to recognize patterns in data that are not apparent to humans at first glance,” Frisch explains. “As an example, algorithms have been developed to identify patients at high risk of sepsis when they first present to the ED so that critical, time-sensitive treatments can be initiated. This early initiation of treatment has shown to improve patient outcomes.”

From Monitoring to Predicting

As machine learning systems and the techniques used to train them become more sophisticated and the algorithms are given access to bigger pools of data, like the information collected in electronic health records, the potential of AI-powered data analytics continues to grow.

Complex machine learning models known as deep learning can process many types of data, allowing them to make predictions as well analyzing existing information.

UCLA School of Nursing Professor and Associate Dean for Research Holli A. DeVon, RN, Ph.D., FAHA, FAAN, became interested in AI and machine learning 10 years ago. “I was intrigued with the idea that you could take massive amounts of data and potentially create new knowledge,” she says.

“ML is a relatively nascent field, and we do not yet know the implications for nursing practice. However, powerful computers and computing software are enabling us to analyze millions of pieces of information, which may lead to improvements in patient care.”

Some examples include clinical decision support tools; triage or risk stratification models; earlier identification of conditions like diabetic retinopathy, breast abnormality and other health problems; and improvements in care delivery.

Using AI analysis, Lee says, offers “meaningful insights into areas that we can improve, looking at the outcomes of our patients when they come here and when they are discharged. There is a lot of information we can work with, so it’s really exciting.”

The Algorithm’s Shortcomings

Although many machine learning models are well-funded research projects, any healthcare applications must be carefully developed so that they can be applied and maintained in useful ways.

“The translation of models to current medical practice is important,” Frisch says. “In using AI in medicine, we usually develop our algorithms on retrospective data, but it is vital for these models to be validated and tested in the real-time clinical setting.”

She adds that it is also important not to “overfit” the ML model, which is where an algorithm learns to performs quite well with the data it was trained with, but not so much with new data.

One problem that has already surfaced in some real-world applications is AI models generating conclusions based on unimportant data, or on correlations that don’t exist outside their training hospital. An example is estimating patient acuity based on which unit or ward a patient is in rather than the data in their electronic health record.

Bias In, Bias Out

Another concern with machine learning is ensuring that it promotes care that is equitable and ethically sound. For example, if care is being delivered today in ways that reflect racial bias, machine learning models trained using today’s data could follow suit. The AI will be no better than the data used to train, validate and test it.

“There is concern that the data being used to train and validate models have biases,” Frisch says. “It is our responsibility to recognize these biases, acknowledge them and determine if there is something that needs to be changed in current practice to potentially avoid these biases.”

“Studies must also be designed to include variables that are relevant to all populations,” adds DeVon. “For example, they must include women and members of minority groups.”

Big Data

To produce useful machine learning models, scientists need access to large, diverse datasets whose data is representative, current, well-organized, “cleaned” (i.e., free of input errors and invalid entries), and validated.

The data must also be de-identified to protect patient privacy and avoid creating additional biases based on irrelevant correlations.

All that is a big job, but, Frisch points out, “models may not have to be generalizable to the entire population, but rather customized to data at a specific healthcare system or region.”

New Roles for Nurses

Nurses should know that machine learning is already here now, and it will be an important part of the future of healthcare. According to a recent report from the research firm MarketsandMarkets, the global market for healthcare AI is expected to grow tenfold in the next few years, from a $4.9 billion industry in 2020 to $45.2 billion by 2026.

“In the future, if you don’t understand how this algorithm works and how it can generate data, it will be hard to be a patient advocate,” Lee says. “So, it’s very important for us to be educated instead of rejecting or trying to avoid it. We have to be really involved and influence the technology developers.”

Nurses can use this technology to their advantage: not to take anyone’s job, but to quickly and efficiently perform tedious, lengthy or complicated tasks.

“Nurses understand the importance of treating the right patient at the right time with the right treatment,” Frisch explains. “AI and ML can augment patient care to ensure that outcomes are maximized without increasing the work burden on nurses.”

AI will also create new specialty roles for nurses with the expertise needed to validate the machine’s work and ensure that it enhances care delivery. Just as nursing informatics emerged as a new specialty, so too will an area of the profession focused on artificial intelligence and machine learning.

“The potential of this technology is endless,” Lee says.

DARIA WASZAK, RN, DNP, CNE, COHN-S, CEN, is a Long Beach native and SDSU and UCLA alumna. She has more than 25 years of clinical and leadership experience and is currently an academic nurse educator and associate dean.

In this Article: Care Management, technology