Feature

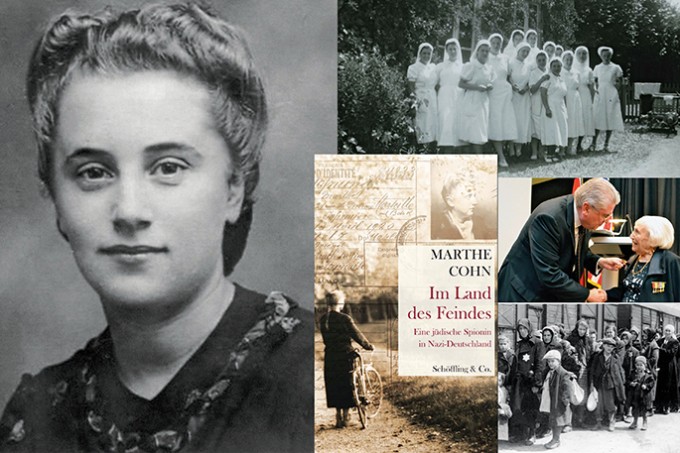

A Sixth Sense for Danger: The Marthe Hoffnung Cohn Story

A Jewish nurse spying in Nazi Germany

Marthe Hoffnung Cohn was an Orthodox Jewish nurse from Alsace-Lorraine who went underground to evade Nazi capture. She worked behind enemy lines as a spy for French military intelligence, and later set up a field hospital in Indochina, where she had to learn anesthesia from a manual.

This is her amazing true story.

Hazardous Crossings

Seventy years after the fact, Marthe Cohn tells the story with a slight smile on her lips, although it is no laughing matter:

“Then, my footing gave way beneath me and I plunged feet first through thin ice into a canal. I went completely under, breaking through before bobbing back up, gasping for air. The water was as cold as death. ‘Come on, Marthe, keep trying,’ I told myself angrily. The temptation to give up and sink back into the water was becoming greater and greater. Closing my eyes, head down, I gave myself one final push on my arms and collapsed on my side into a drift.”

This harrowing incident was only one of her 15 attempts to cross from France into Germany in early 1945. Although she trained as nurse, Cohn — born Marthe Hoffnung — spent the final year of World War II in a far more perilous role: as an agent of French military intelligence, interrogating captured Nazis and conducting surveillance behind enemy lines.

France Falls: Military police scream “Juden raus!”: “Jews Out!”

Alsace-Lorraine is an area west of the Rhine River, which separates France from Germany. Over the years, control of this region has passed between the two countries with surprising frequency. Until 1939, Marthe Hoffnung’s large, “very Orthodox” Jewish family lived in Metz, an industrial city in western Lorraine, about 80 miles northwest of Strasbourg. When she was young, her parents spoke only German, but Marthe and her siblings were bilingual, shifting easily from German to French and back again. This bilingualism, routine for the area and the era, was to serve her well in the years to come.

Just before the outbreak of World War II, the French government directed the Hoffnungs and other Jewish families to move to Poitiers, in western France. At first, life was relatively smooth, but with the fall of France in June 1940 and the ensuing German occupation, most French people soon felt intolerable pressure, from curfews to rationing.

The Jewish population was particularly hard hit. Under the occupation, French Jews faced barriers to employment, were stripped of legal rights and were prohibited from using public facilities or owning radios. Before long, outright threats to their life and freedom became commonplace.

The Hoffnung family business was seized and, in August 1941, Marthe was sacked from her new job at the city hall by German military police officers screaming, “Juden raus!”: “Jews out.” In that climate, envisioning a new career was an act of faith. Marthe chose nursing, in part because her fiancé, Jacques Delauney, a medical student, dreamt that they could work together after the war.

Escape to Vichy: Stephanie Hoffnung is arrested and sent to Auschwitz

Marthe began her nursing training at a nearby Red Cross school run by the nuns of les Sœurs de la Sagesse. At first, things went well. She was under the protection of the head of the school, Mademoiselle Margnat, who knew that Marthe was Jewish and hid the young woman from the German soldiers who periodically came to the hospital to arrest patients.

At the end of her first year, however, Marthe was forced to quit school. In June 1942, German security police had arrested her sister Stephanie, a medical student, for resistance activities and were now holding her in a camp near Poitiers.

Hoping to facilitate Stephanie’s escape, Marthe organized the successful passage of the rest of her family in Poitiers to Vichy, the then-unoccupied French puppet state headed by Philippe Pétain. Nonetheless, in September 1942, Stephanie was deported in a convoy headed for Auschwitz. The family spent years wondering if she had survived, but she was never heard from again.