Feature

250 Years of Black Nursing History

The legacy of nurses who changed the nation

Despite centuries of slavery, segregation, systemic inequality, and prejudice — including being denied entry into nursing schools and organizations — Black nurses have made noteworthy contributions to our profession.

In this article, we’re spotlighting some of the efforts of courageous and determined Black nursing pioneers.

Civil War Battlefields

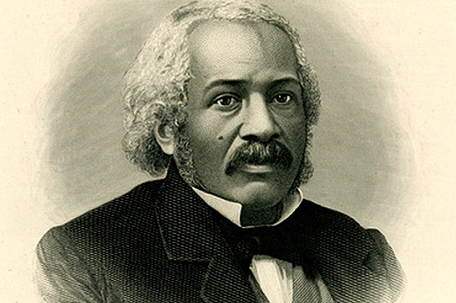

One of the earliest Black luminaries in American healthcare was James Derham (or Durnham) (1762?–1802?). Born a slave in Philadelphia, Derham was purchased by a doctor who encouraged him to study medicine, in an era when it was actually illegal in many states for Black people to learn to read or write.

Derham is believed to have earned enough money working as a nurse to purchase his manumission when he was 21. In the 1780s, he traveled to New Orleans, where he became a nurse for a Scottish physician.

He later became the first Black man in the U.S. to practice medicine, once earning a handsome income of $3,000 a year. However, he vanished and is presumed to have died in 1802 after a new local law banned the practice of medicine by anyone without a formal medical degree — something Black Americans in those days had no chance of obtaining.

A number of Black women born in slavery became nurses during the Civil War. Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), who later remembered having been sold with a herd of sheep for $100, and Harriet Tubman (1822–1913), who once had a $40,000 price on her head for “stealing slaves,” both cared for soldiers during the war. Whether treating wounds or dysentery, they helped to bring comfort and order to places of horror — the only way to describe Civil War battlefields and hospitals.

Susie Baker King Taylor (1848–1912), born in Georgia, was liberated by Union troops in 1862 and became a regimental laundress with the newly organized 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored). Washing and ironing were only a small part of her unpaid work, which also included nursing sick or wounded soldiers using traditional folk remedies like sassafras tea.

After the war, Taylor became president of the Woman’s Relief Corps, a veterans’ association that assisted soldiers and hospitals in civilian life.

In 1902, she wrote a memoir chronicling her wartime experiences, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers. “It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war,” she wrote, “how we are able to see the most sickening sights … with feelings only of sympathy and pity.”

Getting Organized

The end of the Civil War brought an end to the practice of slavery, but not to discrimination. By the 1880s, “Jim Crow” laws had made many activities, areas, and organizations effectively — or explicitly — off-limits to Black people. There were also sharp limits on where Black Americans could study or practice nursing and whom they were allowed to treat.

The first Black woman to work as a professionally trained nurse in the United States was Mary Elizabeth Mahoney (1845–1926), who graduated from the nursing program of the New England Hospital for Women and Children in 1905.

Because the hospital’s policy at the time was that only one Black and one Jewish nurse could enroll per class, Mahoney was not able to receive her diploma until after she had worked as a private duty nurse in the hospital for 20 years! [Editor’s note: You can read more about Mahoney in our “Profiles in Nursing” column.]

After graduation, Mahoney became one of the first Black members of the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the United States, which later evolved into the American Nurses Association (ANA).

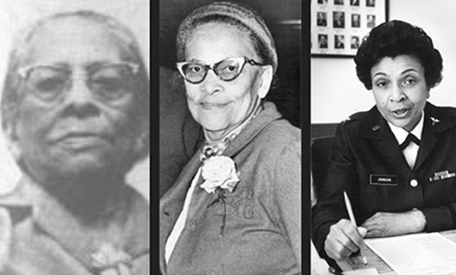

Frustrated by the unequal treatment the Black members of Nurses Associated received, Mahoney, Adah B. Thoms (1870–1943) and Martha Franklin, RN (1870–1968), founded their own organization, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN), in 1908.

Franklin, who became the NACGN’s first president, was also the catalyst for the group’s foundation. Trained at Philadelphia’s Women’s Hospital Training School for Nurses, Franklin was light-skinned and could pass for white. Nonetheless, she became a passionate crusader for integration and better opportunities for Black nurses, sending out thousands of handwritten letters to urge other nurses to join the cause.

Franklin wanted no double standards based on race and insisted that Black nurses meet the same standards set for all nurses. She was also a firm believer in continuing education, entering the graduate nursing program at New York’s Lincoln Hospital and Home so that she could become an RN.

Merging with the ANA

Thoms, the only Black woman in the 1900 graduating class of New York’s Women’s Infirmary and School of Therapeutic Massage, was no less influential. In addition to her work with the NACGN, she spent 18 years as assistant superintendent of nurses and acting director of Lincoln Hospital, which refused to name her to the directorship because of her race. Ironically, that position would remain vacant throughout her tenure because there was no other candidate better qualified than she.

After World War I, Thoms worked for the acceptance of Black nurses into the American Red Cross, a necessary step towards participation in the Army Nurse Corps. In 1921, she famously presented a basket of roses to President Warren G. Harding and his wife, telling them that the 2,000 Black nurses of the NACGN waited to serve.

Thanks in no small part to the NACGN’s efforts, the number of Black nurses in the U.S. doubled between 1910 and 1930. In 1936, the organization established the Mary Mahoney Award to recognize significant contributions to equal opportunities for minority groups in nursing. Thoms was the first recipient of the award, which the ANA continues to confer today.

In 1951, the NACGN merged with the ANA, although only Franklin lived to see it. Thoms and Mahoney were later among the first inductees into the ANA Hall of Fame, with Franklin’s recognition following in 1976.

Public Health Nursing

Another pioneering Black nurse was Jesse Sleet Scales (1865–1956), who in 1900 became America’s first Black public health nurse. Trained in Chicago, Scales moved to New York. After trying unsuccessfully for months to find a job, she became a district nurse for the Charity Organization Society.

Scales was originally hired to deal with tuberculosis in the city’s Black community, which had few healthcare options and a deep-seated resistance to formal medical care. Her work quickly expanded to include everything from childbirth and chickenpox to heart disease and cancer. Her workload was staggering: As she outlined in a 1901 article for the American Journal of Nursing, her caseload in a single two-month period included 156 calls on 41 families!

Scales’ work inspired other organizations to hire Black community health nurses, some of whom were selected based on her recommendation. She was a pioneer in what we now call culturally appropriate care.

Mabel Keaton Staupers (1890–1989), originally from Barbados, became a U.S. citizen in 1917 and studied nursing at Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing in Washington, D.C. Like Scales, Staupers initially focused on battling tuberculosis, which hit the Black community especially hard. She helped to establish the inpatient tuberculosis clinic at the Booker T. Washington Sanitarium and later became executive secretary of the Harlem Tuberculosis and Health Committee.

Staupers also worked hard to improve the status of Black nurses. She joined the NACGN while still in nursing school and became the organization’s executive director in 1934.

Integrating the Army Nurse Corps

During World War II, she led the campaign to integrate Black nurses in the Army Nurse Corps, meeting with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to explain the folly of the president’s plan to draft white nurses while Black nurses were either unemployed or allowed to treat only POWs and Black soldiers. Thanks to that effort, President Franklin Roosevelt ended racial enlistment restrictions for Army nurses in 1945.

Staupers became president of the NACGN in 1949 and orchestrated the organization’s integration into the ANA two years later. In 1961, she published a memoir, No Time for Prejudice: A Story of the Integration of Negroes in Nursing in the United States.

One of the many Black nurses to benefit from Staupers’ work was Brig. Gen. Hazel Johnson Brown, RN, Ph.D. (1927–2011). The daughter of a tomato grower for the Campbell Soup Co., Brown was originally rejected for nursing school because of her race, was told, “We’ve never had a Black person in our program, and we never will.”

She joined the Army Nurse Corps in 1955 and went on to become its first Black chief, overseeing nursing operations at hundreds of Army medical centers, community hospitals, and clinics worldwide. She was the first Black woman to become a general in the United States Armed Forces.

Nursing Education and History

Brown was neither the first nor the last Black American to be turned away from a nursing program on racial grounds. As Mahoney had discovered years earlier, even institutions that were nominally open to Blacks often imposed quotas or admission limits.

Over the years, Black colleges and universities stepped in to fill the void. In 1892, Booker T. Washington established a two-year nursing program at Tuskegee University in Alabama, which in 1941 added the nation’s first midwifery program for Black public health nurses.

In 1948, the School of Nursing’s new dean, Lillian Holland Harvey, RN, Ed.D. (1912–1950), launched Tuskegee University’s first baccalaureate nursing program, which graduated its first class in 1953.

Harvey, who had previously been director of nurse training at the university’s John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, faced many challenges in establishing the program and keeping it funded and operational. The rigid segregation of the South forced many students to seek clinical experience out of state. Harvey secured national accreditation for the baccalaureate program in 1957 and championed the recognition of licensure across state and national borders.

“Let Her Talk”

Mary Elizabeth Carnegie, RN, DPA, FAAN (1916–2008), who had established another baccalaureate program for Black nurses at Virginia’s Hampton University back in 1943, broke a different color barrier in 1948, when she became the first Black nurse elected to the board of directors of a state nursing association.

When Carnegie joined the Florida Nurses Association (FSNA), Black nurses were accorded only “courtesy membership” with, in her words, “no rights and privileges … other than paying dues.” Carnegie had no intention of sitting silently. “When I went to the first meeting, I just talked anyway,” she recalled.

Finally, the other board members ordered her out — and then voted to make her a full member. “Let her talk,” the association’s president reportedly said, “we might learn something!”

Carnegie remained outspoken throughout her career, giving more than 400 speeches and writing more than 85 articles for different nursing journals. She wrote or contributed to more than 20 books, including The Path We Tread: Blacks in Nursing Worldwide, 1854–1994, a project intended to address the exclusion of Black nurses from other books on nursing history.

Carnegie served terms as president of the American Academy of Nursing (AAN) and chairman of the national advisory committee of the ANA Minority Fellowship Program. She received honorary doctorates from eight different institutions and was named an AAN Living Legend in 1994.

Late in her life, Carnegie was interviewed by Hattie Bessent, RN, MSN, Ed.D., FAAN, for Bessent’s 2006 book, The Soul of Leadership: Journeys in Leadership Achievement with Distinguished African American Nurses.

“If I have done anything by taking a stand for racial equality in the nursing profession and making sure that Black nurses are in the literature, having been left out for so long,” Carnegie said, “I feel that I have fulfilled my purpose for having been in this world.”

Many Others

This article can only scratch the surface of the rich history of Black nurses in America. There are countless others who have contributed to the struggle for equality and continue to fight.

In this Article: Black History, Historical Nurses