Feature

A Brief History of Measles and Its Vaccines

Why the "wildfire disease" still remains a serious global threat

1917 was one of the worst years on record for measles in the United States. There were more than 600,000 reported cases that year, and probably at least 2 million more that went unreported. Epidemics swept the country, exacerbated by wartime mobilization that crowded thousands of men together in Army camps or troopships.

Today, measles is like an unwanted houseguest, clinging to the doorframe and stubbornly refusing to be evicted. Efforts to eliminate the disease keep falling short due to incomplete vaccination — made worse in recent years by vaccine hesitancy and the anti-vaxx movement.

Let’s take a closer look at this frustratingly persistent disease and the vaccine that could eliminate it once and for all.

Measles Rap Sheet

Named for the distinctive rash and small red pustules it creates (called “maselen” in Middle English), measles is a systemic viral infection spread by respiratory droplets. Like many viral infections, it becomes contagious days before most patients realize they have it.

Because the virus can survive in the air or on surfaces for up to two hours, measles is extraordinarily contagious, able to sweep through nonimmunized populations with breathtaking speed. The virus’s basic reproduction number can be 12 or higher, meaning that a single infected patient can potentially infect more than a dozen other people, especially in crowded conditions like schools or military camps.

Many Americans now think of measles as a harmless nuisance, but even today, three cases in 10 will suffer some type of complication, which can include diarrhea and secondary infections like otitis media or pneumonia. There are also rarer, riskier complications, like immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), an autoimmune disorder that interferes with blood clotting.

About one in every 1,000 measles cases results in acute encephalitis, which carries a significant risk of death or lasting neurological impairment.

For people already suffering from poor nutrition or immunodeficiency, measles can be devastating, especially if those patients can’t access treatment for potentially deadly secondary infections. In such conditions, the World Health Organization (WHO) says the case-fatality rate for measles can be as high as one in 10. Worse, there’s still no cure or effective treatment other than basic supportive care.

That’s why measles remains a serious global health threat. According to WHO, measles killed 109,638 people worldwide in 2017. Most of the dead were young children.

Inoculation Quest

In the winter of 1755, a Scottish physician, Francis Home, M.D., made the first known attempt to vaccinate patients against the measles. Home recognized, as physicians had for centuries, that measles survivors acquire an immunity to the disease.

As a measles epidemic swept Edinburgh, he cajoled and/or bribed a dozen sets of parents into letting him inoculate their children using blood from measles sufferers in the late stages of infection. Home hoped this would prevent the children from being becoming infected themselves.

This experiment had some success, but not enough to convince Home’s very skeptical patients that it was worth the risk. His next attempt, using nose swabs rather than blood, was not successful at all, and he soon abandoned the effort.

Although Home’s methods were crude, his theory was fundamentally sound. The measles virus, unlike fast-mutating influenza, is highly conserved. There are distinct strains (which modern epidemiologists can now identify and track quite accurately), but their antigenic effect is about the same.

What that means in plain language is that once your immune system produces enough of the antibodies needed to resist one strain of measles, you’ll probably be permanently immune to all of them.

The Attenuated Virus

Almost 200 years after Home’s experiment, Harvard University virologist John F. Enders, Ph.D., who won a 1954 Nobel Prize for his work in the development of the polio vaccine, set his sights on developing a vaccine for measles.

The first step was to isolate the measles virus. Enders’ research fellow, pediatrician Thomas C. Peebles, M.D., monitored local schools for measles outbreaks in hopes of obtaining viable samples. After many failed attempts, Peebles finally succeeded in growing a measles culture from a throat swab taken from an 11-year-old Boston schoolboy named David Edmonston.

From that discovery, Enders and his research team, including Samuel L. Katz, M.D.; Milan V. Milovanovic, M.D.; and technician Ann Holloway, were able to develop an attenuated (weakened) virus, the Edmonston B strain.

Clinical trials soon demonstrated that this attenuated measles virus could safely do what Francis Home had attempted two centuries earlier: produce an immune response in patients, but no infection.

The Live and the Dead Vaccines

While the Enders team was still conducting human trials, two Swedish virologists at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute, Sven Gard and his research assistant Erling Norrby, began developing an alternative: an inactivated (killed) measles vaccine, which Gard believed would be safer and easier to control than a live virus. (Polio vaccine uses an inactivated virus for the same reasons.)

Both the live and killed measles vaccines received FDA approval in March 1963. The live vaccine was licensed by Merck under the name Rubeovax while the first killed vaccine was sold by Pfizer as Pfizer-Vax Measles–K.

At first, the live vaccine seemed the riskier of the two. The Edmonston B strain was very effective in producing an immune response, but tended to cause some non-contagious, measles-like symptoms, which alarmed parents and pediatricians alike. Since the killed vaccine produced no such reactions, some doctors and researchers considered it the safer bet.

Unfortunately, the killed measles vaccine posed dangers of its own, which began to emerge over the next two or three years. Not only was the protection it provided only temporary, the killed vaccine could actually leave some patients with an elevated sensitivity to measles antigens.

Rather than being permanently immunized, those patients risked a more serious “atypical measles” infection, accompanied by inflammation, edema, pleural effusion (fluid around the lungs) and a high risk of pneumonia. Inactivated measles vaccines were pulled from the U.S. market in 1967 and eventually abandoned completely.

Meanwhile, the original Edmonston B strain was gradually replaced by even more attenuated live vaccines with fewer side effects. Merck first licensed the Edmonston-Enders strain now used in all modern U.S. measles vaccines in 1968, under the name Moraten. Thanks to the widespread use of the attenuated live vaccines, the number of measles cases in the U.S. fell from about 450,000 in 1962 to only 86 in the year 2000.

MMR And You

Today, the Edmonston-Enders measles strain is usually combined with mumps and rubella vaccines in a three-vaccine “cocktail” abbreviated MMR. A single dose of MMR vaccine is 95–98 percent effective in immunizing patients against measles.

Because there is a small chance the initial dose may fail to produce sufficient antibodies, modern vaccination schedules recommend two doses, spaced at least four weeks apart. Assuming the patient is at least 12 months old at the time of the first dose, two doses of MMR are usually enough to produce lifelong measles immunity.

Because the measles component of MMR vaccine is a weakened live virus, it can occasionally produce some mild, measles-like symptoms, like fever and rash. There can also be other adverse reactions, like joint pain, which are actually associated with the mumps and rubella components of the vaccine.

However, those reactions pale before the symptoms of “live” measles, mumps or rubella infection, which are far more severe and carry a much greater risk of dangerous complications. The side effects associated with MMR vaccination are usually mild, may not occur at all and — most importantly — can’t be transmitted to others.

That’s crucial because some people, like infant children and immunocompromised patients, can’t be safely vaccinated and must rely on the “herd immunity” provided by the immunized people around them.

Autism Hysteria

What about the autism, the great specter of the anti-vaxx movement? Although a since-withdrawn 1998 paper in The Lancet claimed autism was caused by intestinal disruption following MMR vaccination, no subsequent study has demonstrated any causal link between MMR vaccination and autism.

In Denmark recently, researchers at Copenhagen’s Statens Serums Institut conducted perhaps the most extensive investigation to date, examining data from 657,461 Danish children born between 1999 and the end of 2010.

That study, published on March 5 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, concludes “that MMR vaccination does not increase the risk for autism, does not trigger autism in susceptible children and is not associated with clustering of autism cases after vaccination.”

A Preventable Problem

Nonetheless, vaccine hesitancy is now stymieing efforts to eliminate measles, which had been all but eradicated in the U.S. 20 years ago. WHO recently warned that after years of declining measles cases and deaths, three of the organization’s six global regions “are experiencing a large measles resurgence.”

In 2018, the U.S. had 372 confirmed measles cases, almost as many as in the three previous years combined. This year, there were a total of 206 just in January and February.

“The resurgence of measles is of serious concern, with extended outbreaks occurring across regions, and particularly in countries that had achieved, or were close to achieving, measles elimination,” WHO Deputy Director-General for Programmes Soumya Swaminathan, M.D., lamented in November.

“Without urgent efforts to increase vaccination coverage … , we risk losing decades of progress in protecting children and communities against this devastating but entirely preventable disease.”

Sidebar:

Secondary Killers

In the U.S., the measles-related death toll actually declined long before the measles vaccine became available, falling to 500 deaths a year or fewer by the 1950s. The main reason was penicillin, which can treat the bacterial secondary infections that previously caused most measles-related deaths.

Pneumonia was the single biggest killer. During the measles epidemic that swept U.S. Army camps in 1917–18 — which had a case-fatality rate of about 6 percent, killing 2,370 men — over 90 percent of the deaths were due to bronchopneumonia or lobar pneumonia. However, in the pre-penicillin era, even infections like otitis media could sometimes be fatal.

A nightmare scenario for public health officials would be a major resurgence of measles combined with antibiotic-resistant bacterial pneumonia. Such an outbreak could easily prove every bit as deadly as the measles epidemics of a century ago.

Sidebar:

Razi’s Book

The first text to clinically describe measles was Kitab al-Judari wa al-Hasabah (A Treatise on the Small-Pox and Measles), one of almost 200 books by the multitalented Persian physician Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, who died between 925 and 932 A.D.

Not only did Razi distinguish between measles and smallpox, he recognized them as communicable diseases, a point that remained controversial among European physicians well into the 19th century. Razi’s monograph on smallpox and measles, originally written in Arabic and not translated into English until 1847, has now been in print for over a thousand years.

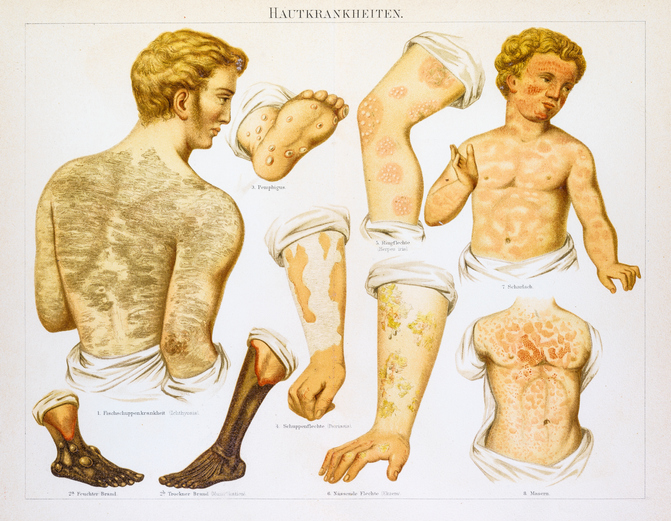

Photo Above: Engravings from Les Remedes des la Bonne Femme, circa 1880, provided a reference to identify measles

In this Article: Measles, Public Health, Vaccination