Feature

When the Nurse is an Addict: Part Two

How to recognize the signs and intervene when your colleague may be under the influence

In many workplaces, they’re spoken of only in whispered breakroom gossip and terse, cryptic warnings from management — staff nurses who’ve been accused of drug diversion, been caught stealing narcotics or who showed up to a 7 a.m. shift with alcohol on their breath.

The chances that you’ve had a colleague who suffered from substance use disorder (SUD) are greater than you might think. The ANA estimates that 6 to 8 percent of nurses use drugs or alcohol to an extent that impairs their performance.

A 2010 study in the Journal of Clinical Nursing cites other estimates as high as 20 percent. That’s one in every five nurses! Could you accurately identify a colleague who’s intoxicated in the workplace? Would you know how and when to intervene and what it takes to genuinely help?

Warning Signs

Because healthcare professionals struggling with substance abuse disorder don’t necessarily fit the common stereotypes of addiction, recognizing the signs of their abuse can be a real challenge, especially in the early stages. A nurse suffering active addiction may appear to be a highly functional, knowledgeable, hard-working overachiever whose outward demeanor scarcely hints at his or her surreptitious abuse of substances to self-medicate physical and/or emotional pain.

Nevertheless, nurses struggling with addiction often demonstrate certain telltale signs. (Keep in mind that these signs alone aren’t necessarily evidence of drug or alcohol abuse. However, when they present as a trend over a period of time, they may indicate a serious problem.)

A nurse who is abusing substances may:

- Become inexplicably irritable, experience labile moods or have angry outbursts.

- Take frequent breaks or leave the department without proper notification.

- Suffer numerous illnesses, increasing tardiness and frequent absences, for which he or she may have elaborate excuses.

Nurses who are diverting meds for their own use sometimes sign up for extensive overtime to ensure easier access to their drug of choice. Where nurses are required to have a witness as they waste narcotics, a nurse who’s diverting might come up with various justifications for wasting drugs alone, such as dropping meds on the floor. Diversion often comes at the expense of patients, who might complain that their pain medication isn’t working or that they haven’t received scheduled doses.

Medical administration records indicating that a patient who hadn’t previously requested anything for pain or sleep is suddenly and frequently asking for meds can also be a warning sign if all the new medication requests are documented by a single nurse.

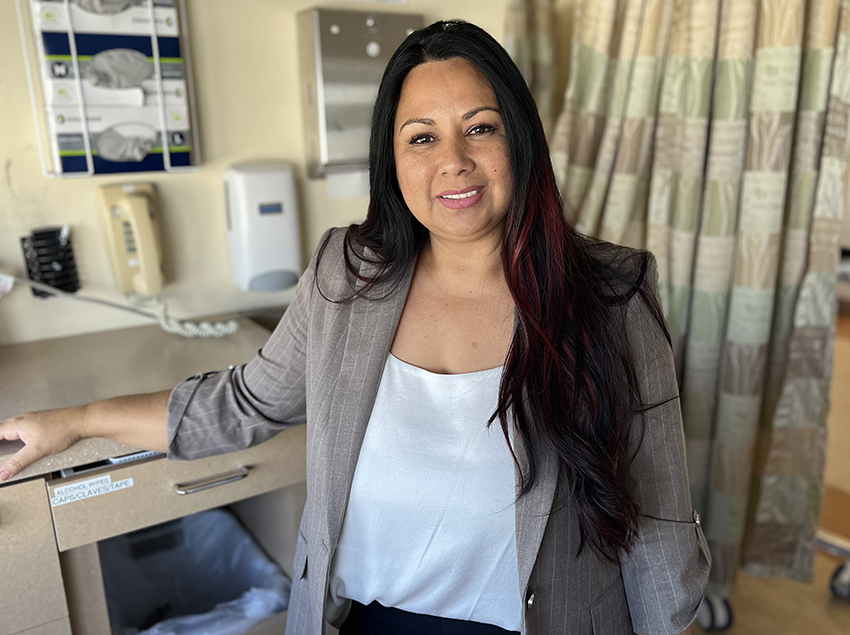

Time to Intervene

Nurses suffering from substance abuse will often go to extreme lengths to hide their secret. By the time a nurse resorts to stealing meds or arrives at work visibly under the influence, he or she is undoubtedly desperate — and perhaps even hoping to get caught. That was my experience. I’d been using Vicodin for years, legitimately prescribed for migraines.

However, my poorly managed stress, job burnout and lack of sleep eventually made the drug an all-encompassing habit. By 2016, I was trapped: physically and psychologically dependent on opioids, long past self-regulating rules such as “never take a pill less than eight hours before work.”