Profiles In Nursing

Evelyn Lundeen (1900-1963), Neonatal Nurse Who Redefined Premature Infant Care

Setting the standards for neonatology care

When Evelyn Lundeen began the job that would become her life’s work, neonatology as we know it was barely practiced in the U.S. When Evelyn Lundeen began the job that would become her life’s work, neonatology as we know it was barely practiced in the U.S. By the time she died almost 40 years later, Lundeen had not only saved the lives of thousands of premature infants, but also helped to elevate the standard of care for preemies everywhere.

Incubators and Innovation

A century ago, babies born prematurely faced grim odds of survival. Most children were born at home, and many hospitals refused to admit neonates not born in that institution. Even if they did, few American physicians studied or practiced the care of preterm infants. Incubators for newborns were widely regarded as carnival gimmicks rather than practical medical technology.

Chicago pediatrician and pediatrics professor Julius Hess, M.D., felt differently. Hess had studied the European literature on caring for preemies, which emphasized consistent temperature and isolation from pathogens. He was also friends with Martin Couney, M.D., a physician and impresario responsible for many sideshow exhibitions of babies in incubators.

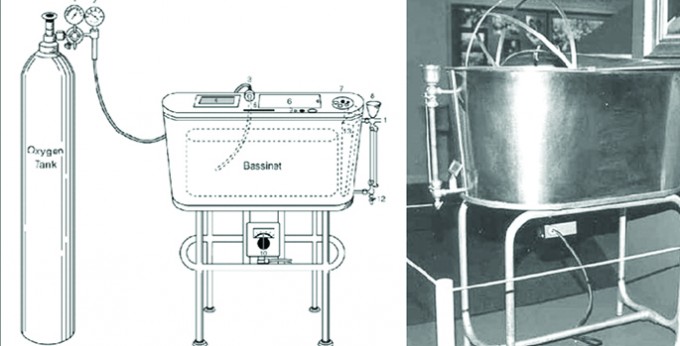

Inspired, Hess developed his own incubator, the Hess bed, an electrically heated device that looked and worked something like a giant double boiler. A few years later, he also wrote the first American medical text on premature infant care. In 1922, Hess received a sizable gift from the Infants’ Aid Society to establish the Premature Infant Care Station at Sarah Morris Children’s Hospital in Chicago — the first station of its kind in the U.S. Soon after, he hired Evelyn Lundeen, RN, a young nurse who’d graduated from Lutheran Hospital School of Nursing in Moline, Ill.