Feature

When a Special Patient Dies

A routine of self-care helps to cope with loss

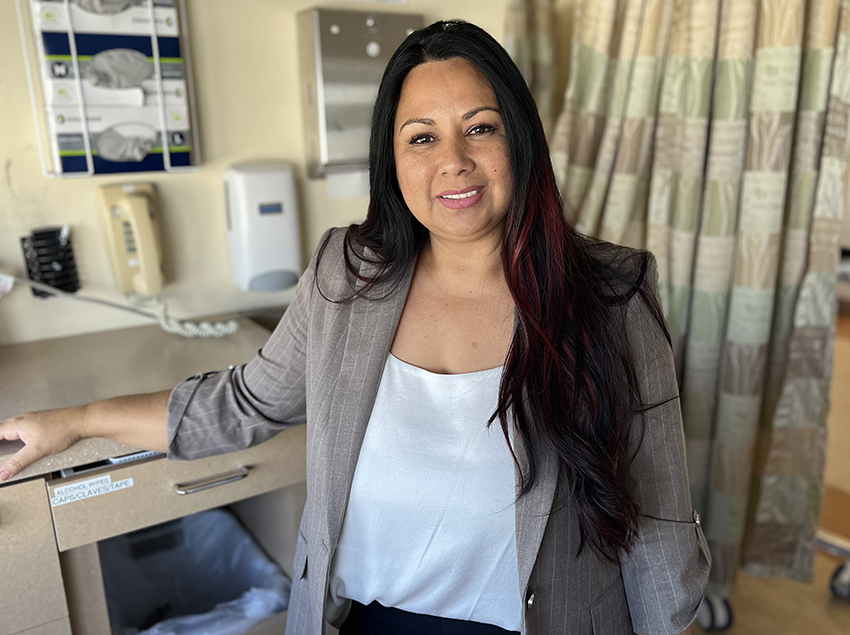

Clocking in for my night shift, I was filled with dread. A longtime patient of mine had been moved to the PICU at the end of my last shift because her septic body was beginning to shut down. She had been ravaged by leukemia. She was 15 years old.

Looking at the assignments that night, my dread was realized: Her name was gone. She had died. I was a new nurse at that point and this was the first time that a patient of mine had died. A week later, I attended her funeral. I hugged her mother as we cried at the front of the church.

I struggled for weeks after her death and had a difficult time finding a way through my grief. It was like a maze — a maze I couldn’t even bear to move through. I wasn’t trying to deal with my feelings because I had no idea how to even begin.

Lessons Learned

My first thought was to escape to the mountains. I normally spend weeks each year hiking through the mountains of California and the deserts of Utah. These are the places that bring me peace. The world makes sense when I’m outside; this is where I process my feelings.

Behind the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles is a trail leading to the top of Mt. Hollywood, a prominent peak that gives a panoramic view of the L.A. basin. There is an overlook with a couple of picnic tables. For me, this hike has turned into a ritual of sorts — a ritual of sweat and fresh air and introspection.

It was through this practice that I came to realize that each one of the patients I had lost — those deaths — had taught me something.

That first cancer patient taught me about happiness. Trite, I know; trite, but true. She taught me that no matter what pain you were going through, you could always smile. She was in and out of the hospital for years, but I didn’t once see her angry or unhappy. There were times I saw her in immense discomfort, but she was still able to tell me a joke.